The most important ingredient in smørrebrød is rye bread,

one of the most significant foods in the history of Denmark

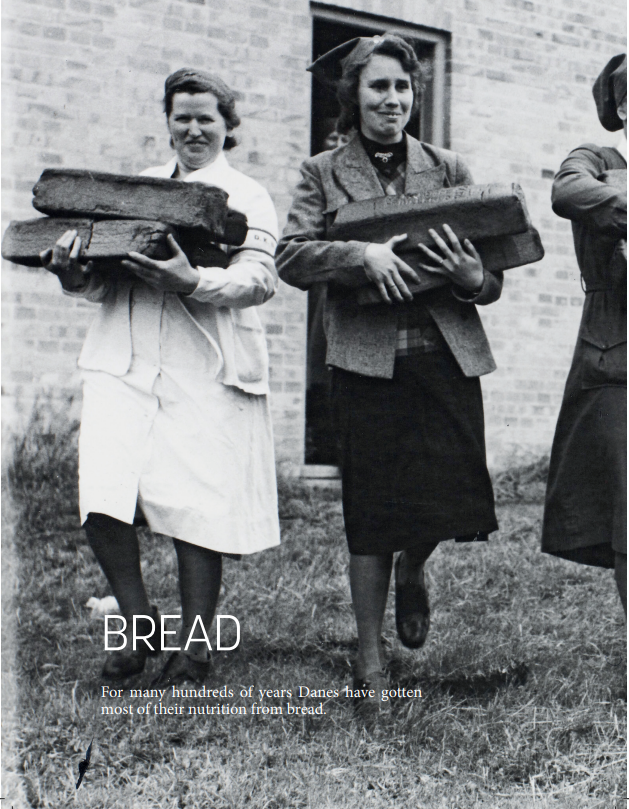

The Danes invented smørrebrød, but they have no claim to being the first when it comes to baking bread. The earliest trace of bread baking in Denmark was found in Jutland in the form of a 2000-year-old clay oven similar to the kind used in the Middle East for baking flatbread. During the Viking age, rye became dominant, the dough was leavened and baked with the use of ovens, making way for rye bread as we know it, and for several hundred years, the word‘bread’ meant ‘rye bread’

As villages and towns formed, central bakeries emerged and people would bring their own dough to be baked. As commercial baking emerged, authorities began to control both the quality and the price of bread. There were examples of unscrupulous bakers who would add foreign objects like sawdust to keep costs down, and some would use portions of lesser-quality barley without declaring it. So laws were passed to regulate how much rye a loaf of rye bread must contain, and the bakers were obliged to stamp their official seal on their bread. Thus, it was easier to investigate fraud; if caught, perpetrators would be heavily fined. If the crime was repeated three times, the baker’s oven would be taken apart and destroyed. Bread was serious business.

For the common Dane, bread was synonymous with rye bread. However, in the late 1600s, white wheat bread started to appear in Denmark, inspired by baking in the Netherlands and France. Since everything French became fashionable in the 1700s, the bread became known as franskbrød meaning ‘French bread’. The common people, however, called it ‘cake’, as it was a luxurious treat often made with milk and egg.

For hundreds of years, Danish rye bread has been made predominantly with rye, sometimes mixed with a small quantity of wheat to introduce a slight airiness and soften the rather distinctive rye taste. Rye bread has generally been put into two categories: one just called rugbrød, and the other called fuldkorns rugbrød, which means that the flour has been mixed with whole grains.

‘There are people who think that smørrebrød is good if it has good toppings. This is wrong. The secret to fine smørrebrød is very simple; it doesn’t matter what is on the bread, as long as the bread is good.’

– Mogens Lind, poet and influential gastronome, 1947.

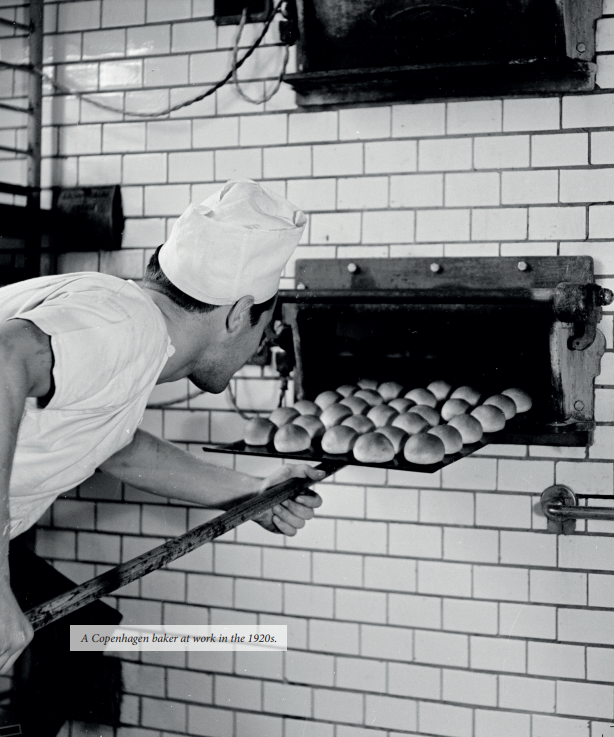

Up until the late 1800s, rye bread was leavened with sourdough. In 1880, though, this technique was altered thanks to the efforts of entrepreneur Viggo Schulstad, who founded Copenhagen’s first industrialised bread factory. The rye bread in those days had a markedly sour taste. One might humorously suggest that this was because the dough had been kneaded by barefoot men, which was actually the case, but this method was replaced by Schulstad with modern kneading machines.

The sourness was due to the use of sourdough as a leavening agent, something Viggo Schulstad abandoned as he shifted to a new method based on baker’s yeast, a modern invention made possible by Louis Pasteur’s research in the 1860s. By combining yeast and sweet malt extract, Schulstad achieved an efficient leavening without the sour taste.

This type of rye bread was slightly sweet. It became very popular and eventually altered the Danish style of rye bread. This was partly because of the sweeter taste and partly because the industrial bakeries used a square baking tin which produced square bread. The shape of rye bread had previously been more oval, round, and large. The modern square form was efficient during production, and in those years when packed lunches became popular, it was much easier to pack the square slices.

Bread factories similar to Schulstad’s became dominant over the years, especially as supermarkets gained popularity. Small bakeries co-existed successfully and were generally known for a higher quality than the industrial bread that most Danes ate for lunch.

In those days, rye bread was not coveted: it was mainly a vehicle for toppings, and it would generally be cut in thin slices, especially at restaurants. Rye bread was an obligatory ingredient under the toppings, seldom praised in its own right. The majority of rugbrød was baked at a few factories since the baking industry had been consolidated.

From the 1940s to the 1990s, you would find the same type of industrial rye bread in most of Denmark’s smørrebrød restaurants. Nobody cared if it was fresh, and it was often several days – or even weeks – old. But a development began in the 1980s that saw more types of bread become available as Danes started taking a bigger interest in taste than ever before. Gourmet restaurants became more numerous, and this started to rub off on bakeries, which began introducing more exotic types of bread. At least, the names were exotic. The bread was usually a product made with instant mixes given to all bakeries by the same few suppliers. In essence, a focus on craftsmanship was close to non-existent, although the bakeries made a point of calling themselves ‘artisanal’.

There were a few exceptions. In Copenhagen in particular, you could find small, independent bakeries that delivered high-quality bread to the relatively small group of discerning customers who took delight in its quality. One of these small, artisanal bakers was Reinhardt van Hauen, which was regarded as one of Copenhagen’s finest. This reputation lasted up until around the 1980’s, when new competition arrived.

One of the pioneers in what can be called the ‘bakers’ revolution’ was the young baker Ole Kristoffersen who opened for business in 1991. He was one of the first traditional bakers to stop using the industrial ready-made mix that dominated the business. Instead, he focused on a more artisanal style. He demonstrated his commitment to craft by moving the kitchen – traditionally hidden in back – inside the shop so that customers could follow the baking process. He also introduced a new type of stone oven which further improved quality.

Five years later, the bar for quality rose further when respected gourmet chef Per Brun entered the business. He bought an existing bakery and started to sell a sourdough wheat bread made entirely without yeast, which was very unusual at that time. Brun had developed the recipe over several years at his gourmet restaurant before entering the bakery business and causing a stir. His bread cost three to four times more than regular bread.

But it was also much tastier. His bakery, Emmerys, grew into a small chain focusing on gourmet-style bread and cakes. It became very successful in Copenhagen as the first gourmet bakery chain, and its 100% sourdough wheat bread was perhaps its greatest success. This seemed to inspire Ole Kristoffersen at Lagkagehuset. He began offering a version with a fraction of yeast added to the sourdough. This yielded a similar quality and was favoured by many customers.

It is tempting to draw a parallel to Viggo Schulstad’s transforming of the rye bread tradition. Just as Schulstad eliminated the sour taste and gained enormous success, so did Kristoffersen’s bread, less sour than that of Emmery’s. By then, the bakery landscape in Denmark had changed. The 3,800 bakeries that flourished in the 1960s had dropped, by the 1990s, to just 800 shops. The losers were the old-fashioned bakeries that relied on industrial ready-made mixes, and the winners were the small, new, gourmet-style bakeries.

Gastronomic entrepreneur Claus Meyer, the co-founder of the restaurant Noma, also entered the bakery business and helped raise the level of bread quality. He was active in Copenhagen where most of the new bread action took place. But out in the provinces, in South Jutland, a baker named Steen Skallebæk gained attention by operating a very successful local bakery that was comparable to Ole Kristoffersen’s Lagkagehuset in Copenhagen.

In 2008 Ole Kristoffersen and Steen Skallebæk decided to join forces. While the elite-oriented chain Emmerys suffered bankruptcy and was restructured, Ole and Steen were successful with a style that was less geared toward the elite class but still outclassed the average Danish bakery.

They seemed to have found the perfect recipe for growth as they embarked on an extensive expansion that as per 2020 has reached most parts of Denmark with 103 outlets. They helped lift bread quality remarkably, not only in the big cities but also in smaller towns, something no one had done previously. In 2016 Lagkagehuset, under the new brand Ole & Steen, expanded first to London and then to New York, successfully introducing Danish rye bread as well as pastries and smørrebrød.

There have been several attempts by Danes to go abroad and establish authentic bakeries or smørrebrød restaurants, but few have succeeded. With years of success selling rye bread and smørrebrød, Ole & Steen are the first to prevail in this regard.

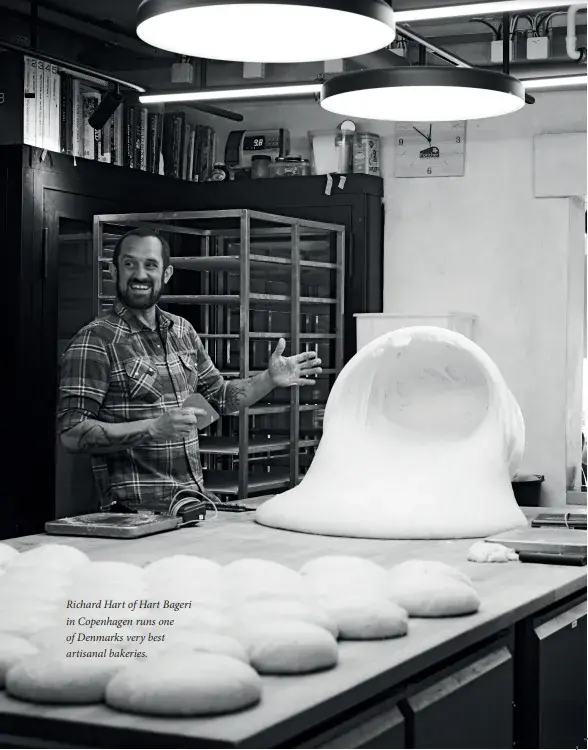

Lagkagehuset raised the bar for quality bread all over Denmark, but since then, new leaders have emerged, like Batting Bakery, Juno the Bakery, Lille Bakery and, recently, Hart Bageri.

Hart Bageri is run by Richard Hart – former head baker at famous American bakery Tartine in San Francisco – and backed by Noma co-founder René Redzepi as co-owner. Most of these new bakeries are run by chefs, several of whom are Noma alumni. This is a good indicator of the strong forces that have joined the Danish bakery revolution and developed the trade over the last 30 years.