Directly translated, smørrebrød means ‘buttered bread’. After bread, butter is the second most important ingredient. If you leave it out, it simply isn’t smørrebrød.

Why is butter important? Chiefly because it tastes good when it is fresh and made well from good milk. This is not a given, as butter comes in many quality grades, and sometimes you will be served ‘butter’ that isn’t even butter but is rather margarine or a mix of butter and oil. Butter also enhances the taste of bread and toppings, so removing the butter from smørrebrød is like removing the seats in a car, the heels on a pair of stilettos, or the sunshine from summer.

Traditional rye bread needs a layer of fat to become really delicious, and butter builds a connection between bread and the toppings, bridging both taste and structure. Also, the butter layer prevents the bread from becoming soggy. This was an important function during the hundreds of years when Danes would bring smørrebrød to work or school, which everybody did until recently when competition arose from new food places like burger bars and pizzerias.

Butter has been around for about 5,000 years. The Vikings called it smør, which is related to the English smear, meaning ‘fat stain’. But where the English adopted a version of the northern word for bread, which is brød, they leaned toward the Greek word for butter: bouthyron.

The Vikings were known to bring bread and butter along on their voyages, and they produced butter in England during the Viking reign, which lasted from around the year 800 to 1000. Once they rid themselves of the Vikings, the English, it seems, were able to turn to more trivial matters such as the quality control of butter. Around this time, the English King Athelstan issued a law making it a crime to falsify butter, this law later inspired certain local communities in Denmark to impose similar laws. In the following centuries, butter became abundant in Denmark; in 1128, the Danish Bishop of Lund had an entire ship loaded with butter to send to his German colleague Otto von Bamberg.

Butter was a seasonal product, since milk was only available in summer when the cows had calves. So it was important to conserve the milk for use in the long winters. This was done by making cheese and butter, and the latter was most popular in Denmark for hundreds of years until the Dutch technique for cheesemaking became known to the Danes.

Until then, butter was the preferred conservation method, and it was kept in a salty brine where it could be preserved for months.

Every farm would make its own butter by collecting the scant cream from the milk over several days and waiting until there was a sufficient amount for churning. Niels Henrik Lindhardt from Aabybro Dairy, whose family has been making butter for generations, describes this process:

‘In the old days, the wealthiest of peasants had a cow or two which they would milk daily, skim off the cream, and leave it in a warm place in the house. This was repeated daily until there was a bucket of cream, which would naturally go sour. This soured cream would be put in a small wooden churn, a kind of wooden barrel with a lid, in which the cream would be stirred with a wooden pole until it sometimes separated into butterfat and buttermilk,’ says Lindhardt, smiling as he explains.

‘It did not always work, since there were several factors that needed to be in order. For example, it was important that the woman operating the churn had fastened her skirt to the left, and it certainly helped if she possessed the gift of ‘butter luck’, something that could be enhanced if she, as a small baby, had been holding a churn stick while she nursed. Another important factor was to avoid witchcraft, and this could be helped by placing a toad under the churn. People simply did not realize that if the cream went past sour and into the rotting state, it could not be made into butter. My great grandmother didn’t either, but in the next generation, they got wiser thanks to the technical developments,’ says Lindhardt.

Historically, there were two quality distinctions: ‘peasant butter’ and ‘mansion butter’. The mansion butter came from large farms with big supplies of milk that made it possible to produce the butter from fresh cream, whereas peasant butter could often be stale due to the previously described production method. In general, Danish butter was not very good 150 years ago. In England, Danish butter was called ‘mast butter’ to signal that it was best suited to greasing the wooden masts on ships. Often, merchants would sell Danish butter under names that concealed its origin. One name, ‘Kiel butter’, was taken from the German port south of Denmark from which butter was often shipped.

The foundation for the breakthrough and worldwide fame of Danish butter was likely the investment in the education of farmworkers. In the 1700s, the first institution for the education of farmers and the promotion of new knowledge was formed. Later, via the Folkehøjskoler or ‘Folk high schools’ established around 1850, there was a new education system aimed at adults, helping to build a workforce that had more skills and knowledge than ever before.

The quality of Danish butter began to improve, along with the export market, which started to boom in 1879 when butter from Denmark won the two highest prizes at a butter competition during the International Agricultural Exposition in London. But the real breakthrough in Danish butter production came in 1882 when a small group of farmers in the Jutland town of Hjedding joined forces. They established a communal dairy centred around a newly invented machine that separated cream and milk automatically.

The communal dairy in Jutland was successful. Soon, other milk producers around Denmark followed its example and set up their own communal dairies, which became the norm in the industry. Butter exports exploded from 12,000 tons in 1882 to 78,000 tons in 1900, making one of the world’s smallest countries into the world’s largest butter exporter.

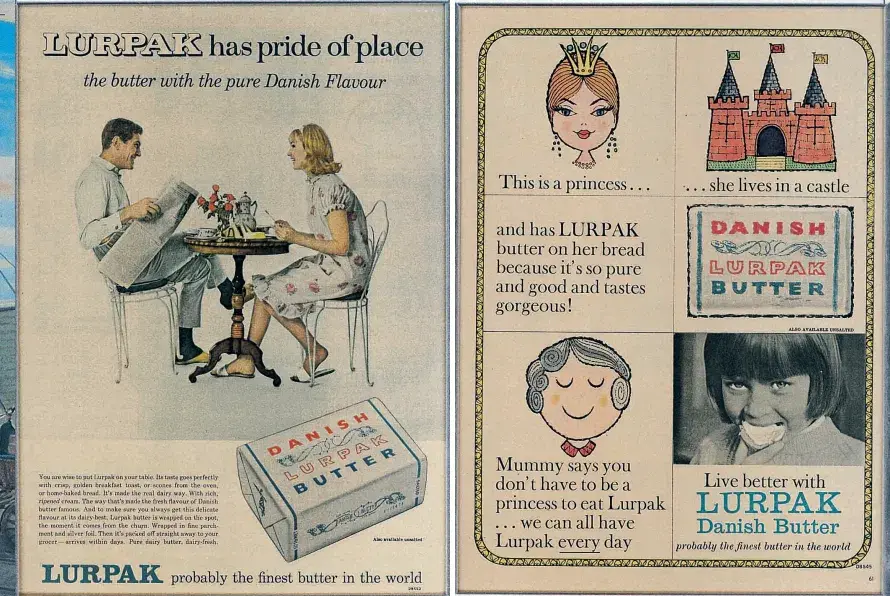

No longer was it necessary to sell Danish butter as ‘Kiel butter’. The previously unwanted Danish butter would now sometimes be counterfeited, when butter from other countries was sold as being Danish. This led to a group of producers establishing a private association with strict quality controls. It attracted almost all of Denmark’s dairies, and around the year 1900, more than 1,000 individually-owned butter dairies would export their products under a common brand: Danish Butter.

To use the brand name, the butter had, of course, to be made in Denmark. It also needed to be made from pasteurised cream, contain 80% fat, and have nothing added to it but salt. Also, the flavour quality had to be very high to meet the strict standards laid out by the team of inspectors roaming the country by bicycle and horse carriage to visit the dairies. This control system made the producers aware of the importance of quality: they risked losing access to the lucrative export markets if they did not live up to the organization’s criteria.

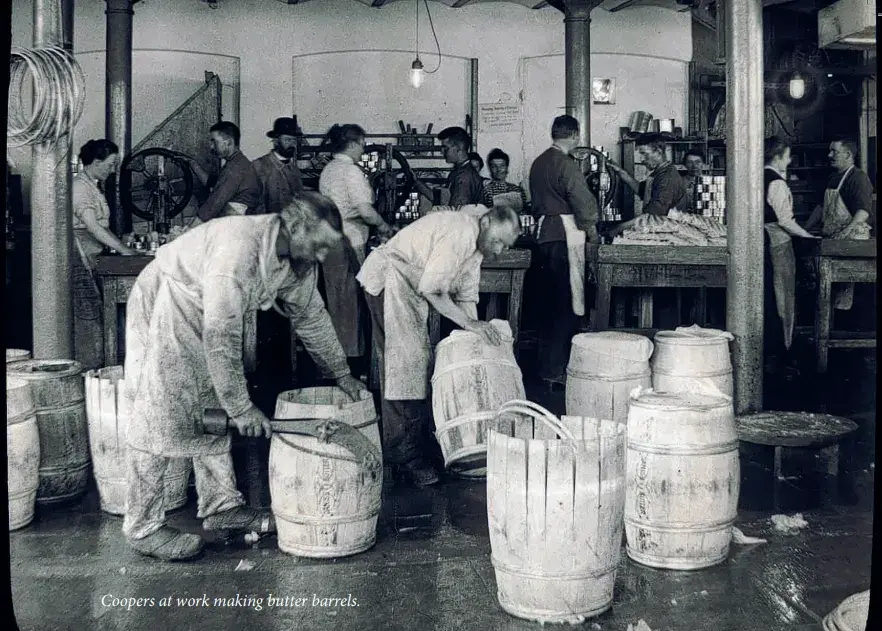

The system worked. It enabled the Danish Butter Association to maintain a high and uniform standard even though the product was delivered by more than 1,000 different dairies by the 1930s and 1940s. The Danish Butter Association took a Bronze Age musical instrument called the lur as its logo, and it imprinted the Lur brand name on the wooden barrels in which the butter was transported. In 1906, the Danish government introduced a law declaring that only Lur brand butter was allowed for export. This law further cemented the quality control of exported butter.

The quality control was very strict. Inspectors would make unannounced visits to milk producers throughout Denmark to check if the quality of the milk was satisfactory. And every week, a thorough control tasting of the finished butter was arranged. Here, a number of trained butter judges would blindly taste and evaluate whether the quality lived up to the established standards, and this method continues to this day.

Control of Lurpak butter is not based on personal preferences but rather on a defined set of characteristics and technical qualities, explains Lars Johannes Nielsen, who is in charge of the control tastings. ‘When we perform the tastings, it is not so much about taste preferences, as about technical quality. The judges performing the assessment have been trained and tested to make sure they know and can taste the nuances in butter flavours and off-flavours, and that they do not judge based on their personal preferences,’ says Nielsen.

To be precise, the judges must evaluate the butter to make sure it meets several criteria: ‘In the assessment of Lurpak butter, the judges must relate to a specific set of instructions, regarding appearance, taste and texture. They are trained and know exactly how Lurpak should look, feel, and taste. A pure, fresh and creamy butter flavour, smooth appearance, and consistency are key to Lurpak and thereby the key to a good grade. These characteristics are all described in the instructions for each butter type. Unsalted butter has one set of rules, salted another, organic butter a third, garlic butter a fourth, and so on. Organic butter is made from cows given a special organic feed, and this is something the judges must consider. For example, a cow given lots of grass in the summer will have this feed shine through in the taste,’ Lars Nielsen explains.

Lurpak butter is by far the most sold and exported Danish butter, but when blind tastings with consumers or chefs are arranged, Lurpak is far from a guaranteed winner.

‘If you put 30 consumers in a room and serve Lurpak and more artisanal types with extra salt and sourness, these may often win since they have a much more defined taste, as do the special Lurpak variants with extra salt. But in the long run, the traditional Lurpak varieties are the most popular, because the quality is consistent,’ says Nielsen.

Comparing the classic Lurpak butter to the artisanal types, is almost like comparing apples to pears. They are two very different things. And while in some cases you may prefer the rich, slightly sour, and extra-salty taste of artisanal butter, in others you may enjoy the clean taste of fresh cream that you get with unsalted Lurpak butter.

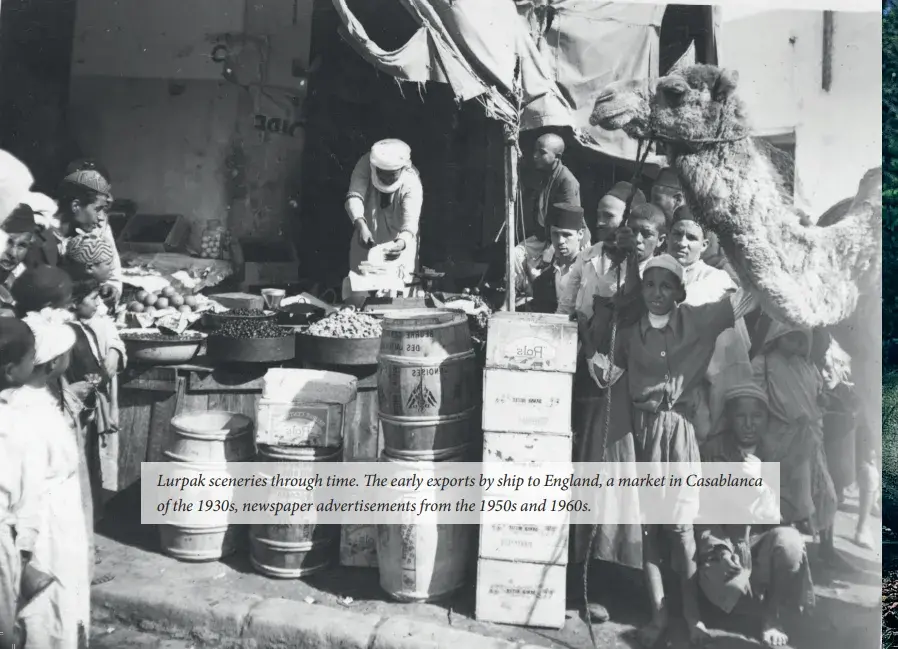

To a large extent, the story of the Lur brand is also the story of Danish butter in general because the Danish Butter Association controlled almost the entire production of butter in Denmark since the Lurbrand’s creation in 1901, and over the next 50 years, it came to set a world standard for good quality.

Lurpak butter spread to most parts of the world, packed originally in wooden barrels for closer markets and in tin cans for longer journeys. In the 1950s, a new, more hygienic packing system replaced the old-fashioned 50-kilogram wooden barrels with 250-gram portions. In 1975, another new technology, the continuous butter-making machine, improved quality even more. Instead of feeding the machinery ‘soured’ cream it was fed fresh cream, which had the souring fermenting bacteria added afterwards, a technique that made it possible to produce larger amounts faster, further diminishing the risk of oxidising the butter. It increased freshness, but at the cost of some of the depth of flavour of old-fashioned butter, where the cream is ‘soured’ – or fermented – for 24 hours before entering the churn.

The continuous butter-making machines have the advantage of operating very quickly and precisely, which is ideal for large-scale production since it assures a consistent texture. Old-fashioned traditional churns have a much smaller capacity, and the quality of the butter varies, but it often has a richer flavour with more aromatics and acidity. Also the structure of the old-fashioned churned butter is less even than that of butter made with the continuous butter making machines which produces a more even and firm texture.

But in the 1980s and 1990s, a growing number of consumers started to ask for organic dairy products, just as old-fashioned churned butter gained popularity among chefs at gourmet restaurants and among discerning consumers. This created a following of customers who cherished the strong and well-rounded taste of old-fashioned butter, which would never have passed the technical quality control of Lurpak.

One of the small dairies that stopped delivering butter to the Lurpak association was Aabybro Dairy, as owner Niels Henrik Lindhardt explains.

‘In 1984, we left the Lurpak since we could not live up to the new quality demands without investing in a continuous butter maker. With this machinery, you can obtain a much longer shelf life than our butter. That is important for Lurpak, which is sold all over the world, but not for us, since we sell our butter locally,’ explains Lindhardt, who found a niche in supplying the butter to restaurants in large catering packs. With this he introduced a new product that inspired many other producers, both small and large. Aabybro Dairy was also a pioneer regarding the now-popular type of gourmet butter made with the addition of large salt flakes. Aabybro Dairy uses a special salt from the island of Læsø, but others have since made similar butters with other types of salt, and Aabybro has won many local competitions with this butter.

Another small player, Øllingegård Dairy, was similarly successful in 2006 and 2008 when they entered their organic butter and won at the international butter competitions arranged by the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association.

These small producers were following in the footsteps of Lurpak, which became famous by winning prestigious titles more than 100 years ago. Lurpak has continued to win titles to this day. The latest victories came at the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association competition in 2020: Holstebro Mejeri won for the best unsalted butter, and Bornholms Andelsmejeri placed second in the salted category.

The traditional Lurpak suppliers – all farmers who jointly own Denmark’s largest dairy producer, Arla – were slow to adapt to the new market demands for organic milk and butter, since organic milk has a distinctive taste that does not fit into the list of rigorous standards for Lurpak. Eventually, though, they acceded to the market demands, and Arla introduced an organic butter as well as other special butters that match the quality of most small competitors.

Since 2012, the Lurpak brand has been owned by Arla. They keep the traditions for rigorous quality control alive by entrusting the control process to an external industry organisation, called the Danish Dairy Board, which monitors the quality. With a market share of around 50 %, Lurpak is the largest butter brand in Denmark but far from the only one. There are a number of small independent dairies, a few of which manage to maintain an independent profile and sell products under their own label while simultaneously delivering milk to the large Arla dairy.

Outside of the Arla circuit are small, respected butter producers like the previously mentionedÅbybro Mejeri and Øllingegård, as well as Ingstrup Mejeri and Naturmælk. Naturmælk is, following Danish dairy tradition, owned by a collective of 33 farms that supply milk. All these producers are organically certified, and a number exceed organic requirements by also following biodynamic principles.

Deciding which butter is best is a daunting task. Those who prefer the old-fashioned style may find Lurpak nondescript, while Lurpak fans may find the old-fashioned butters too rustic. The dilemma is like asking which is ‘best’ between a painting by Renoir and a photograph by Henri Cartier Bresson. I dare argue that no matter how you look at it, it is very difficult to find Danish butter that is not high quality.

And please remember: if the bread is not buttered, it may taste nice, but it isn’t smørrebrød.