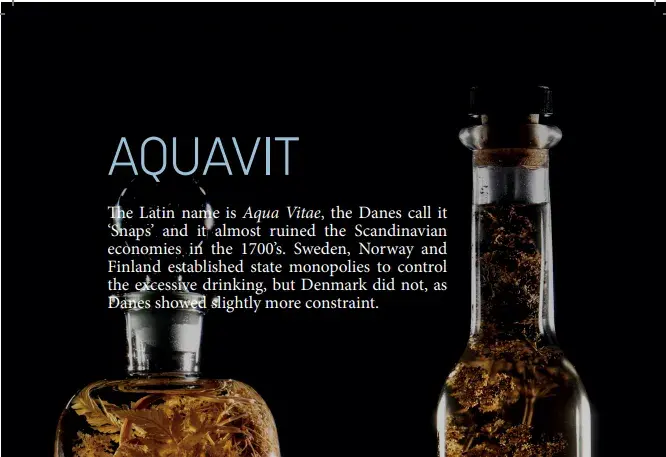

An important part of a traditional Danish lunch is aquavit: the strong spirit that is to Scandinavians what vodka is to Russians and whisky is to the Scottish and locally called snaps

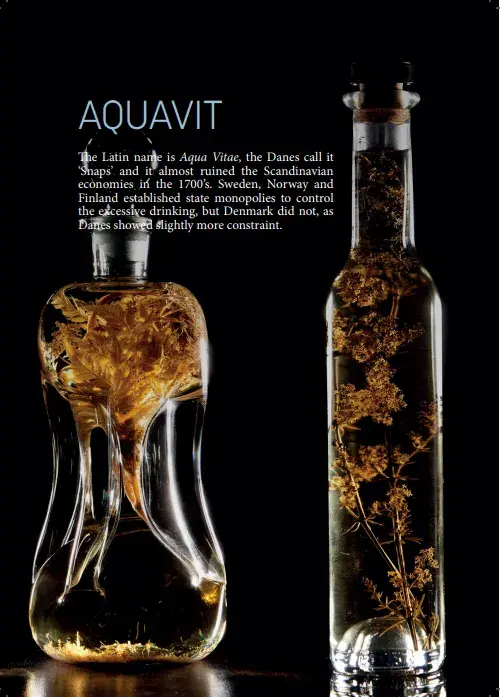

In Denmark the technical definition for aquavit is alcohol made with a destillate made with caraway or dill. Often a variant is made, where the herbs are not distilled but infused, and technically this is not aquavit but snaps.

The original meaning of snaps is ‘a small mouthful’. This gives the term some resemblance to the Russian vodka, meaning ‘little water’. The Swedish call aquavit brännvin, the Norwegians brennevin, and the Icelanders brennivin. This points back to brandy, which originates from when the Dutch merchants distilled wine – i.e. ‘burned’ it – to concentrate the alcohol, making it easier to distribute. This, incidentally, inspired the French to invent cognac, but that is a different story.

In this book you will find use of both the words aquavit and snaps, just as the Danes in general does not discriminate between aquavit and snaps. If you ask for either at a restaurant, you will probably be offered the same; a strong alcohol with some kind of herb flavour. The most common spice has historically been caraway, so for hundreds of years, the taste of aquavit was generally also the taste of caraway. But alongside the caraway aquavit, there is also an old tradition for homemade variants where neutral spirit is infused with a long list of herbs.

Within the last 10 to 30 years, however, the taste of aquavit has evolved with more possibilities, and only now has it entered the gourmet era. This is thanks to the craftsmen at the distilleries who know how to combine many types of spices, berries, fruits, nuts, leaves and flowers to help make the different aquavit flavours akin to fine eau de vie like whisky and cognac.

Aquavit was introduced in Scandinavia around 1400, and the earliest source in the Danish language referring to it is a book from 1555 written by a medical doctor. Around that time, aquavit – from aqua vitae, Latin for the ‘water of life’ – was considered a medicine used to treat many diseases. During the 1600s, the popularity of aquavit grew and grew, as did the consumption of it in all of Scandinavia.

In Denmark, one in every five families possessed their own spirit still for making alcohol but the collective understanding of the chemical processes involved was very limited, resulting in spirits with many faults and foul-tasting, poisonous substances like fusel oil. This was probably the reason for adding spices to the aquavit, rather than consumer demand for the taste of the dominating spice, caraway.

Given time, aquavit started to pose an enormous problem: it became a serious threat to the country’s economy, as the workforce was often not able to work due to drunkenness. Furthermore, the side effects of drinking aquavit gravely impaired the health of the population. This led to a ban on home distillation in the 1600s. From then on, permission from the king was necessary if you wanted to distill spirits. This permission was given to a number of inns around the country, who in turn paid tax. Later on, the rules were tightened further, and in the1800s, a school for distillers was established. It became obligatory to take a course before being allowed to open a distillery.

Around that time, the Crown strengthened its grip on illegal distilleries and offered them a deal. If they voluntarily gave up their copper stills, they would not be punished, and on top of that, would be paid for the value of the copper. This yielded no fewer than 11,000 copper stills, and given that the population was around 2 million, added up to one still per 181 Danes.

After this purge, Denmark had 800 official distilleries: a number that dwindled when, in 1881, a new conglomerate started to monopolize spirit production. This was Danish Distillers – De Danske Spritfabrikker – whose driving force was the former distiller Isidor Henius.

Henius introduced a new technique that created the first spirit free from the poisonous fusel oils. Henius became the most important person in Denmark’s spirits industry, and his efforts to consolidate the distilleries achieved success in 1923. In that year, Danish Distillers became the sole producer of spirits in Denmark, and started to build a reputation and garner high acclaim for Danish aquavit in international markets.

It is a popular belief, even among Danes, that Danish aquavit is made from potatoes. This belief is not altogether correct. Even though potatoes started to play a small role in alcohol production during the 1700s, grains were the most common base for aquavit. But in the 1800s, potatoes became increasingly popular, and in 1838, the first dedicated potato-based distillery in Denmark was built. This was the birthplace for what would become the country’s most popular aquavit: Aalborg Taffel. However, potatoes stopped being used as the base for spirit in 1990, because they were too expensive.

Economics was also a factor in making aquavit the most important component of Danish drinking habits for hundreds of years, since imported spirits were heavily taxed. Taxation made imported spirits like whisky and gin cost two to four times the price of Danish aquavit.

But when Denmark joined the European Common Market in 1973, the tax laws changed, making imported spirits more affordable and making it easier for foreign spirits companies to begin aquavit production in Denmark. This was not attractive, however, as Danes were beginning to lose their thirst for aquavit for the first time in hundreds of years. Aquavit began to fall out of fashion in the 1980s with the younger generations regarding it as a drink for old people. The market shrank gradually as older consumers passed away and were no longer replaced by younger ones.

However, the market remained lucrative. Even though the Danes had stopped drinking aquavit daily with breakfast, lunch, and dinner like they commonly did from the 1700s up to the early 1900s, it remained popular with traditional Danish festive lunches. Furthermore, though aquavit became unfashionable in the 1980s, it enjoyed a second wind with the smørrebrød renaissance in the 2000s.

Alongside smørrebrød, aquavit slowly gained popularity, and new small producers started to appear and swell the category’s ranks. One of the first movers and shakers in this new wave was Dan Schumacher. He was not an aquavit professional but rather a chef with a strong interest in aquavit. With this interest came his desire to contribute new inspiration to the old aquavit category which had hitherto been dominated by the taste of caraway. Instead of using distillation, he infused a ready-made alcohol with herbs: a technique that had been traditional in many private homes for centuries. In 2001, Schumacher created a chili and lemon snaps which soon caught on, and soon his products were carried by hundreds of Danish restaurants.

The next wave in modern aquavit production came when some of the newly established microdistilleries – mostly founded in the 2000s and 2010s – took a liking to aquavit. The very first to bring back aquavit distillation to Copenhagen, where it had ceased in the early 1900s, was Henrik Brinks. Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, he was a member of the very generation that abandoned their parents’ drinking traditions by shying away from aquavit.

‘I hated the stuff,’ says Brinks, who defined himself as a ‘whisky man’ during the many years he dreamt of opening a distillery. In 2014, he followed his dream, quit his daytime job as an attorney/consultant, and founded Copenhagen Distillery, which by the way was awarded the title Danish Whisky of the Year 2021 by whisky guru Jim Murray.

‘Yes, I was one of the many young people who really did not like the taste of caraway, and as imported spirits became cheaper, there was really no reason to drink the Danish aquavit, we figured,’ explains Brinks about his generation’s abandonment of aquavit. But one day he was approached by a young bartender, Sune Urth, who suggested that together, they take a shot at modernising the aquavit genre: ‘At first, I was reluctant, but Sune convinced me that aquavit could have a whole other dimension than the one we knew, so I decided to give it a chance. And soon I realised we were dealing with a hidden gem: a forgotten treasure that is actually the soul of Denmark’s spirit heritage.’

‘We started out with a take on the classic Taffel Aquavit, but instead of potatoes, we brought another old, popular Danish crop in play, the sugar beet, and combined it with grain spirit. The sugar beet gave the spirit a certain tough edge, and the only spice we used was caraway. It was as old school as it gets, but the taste was so different than what I had ever experienced before,’ says Brinks, who enjoys serving aquavit to guests at the distillery.

‘We arrange many tastings. Whisky is the most popular, and often I hear somebody say when they look at the aquavit bottles that they hate the taste of aquavit. The same people sometimes praise the ‘welcome drink’ they are served when arriving, and they are all very surprised when I tell them it is actually aquavit,’ laughs Brinks. Truth be told, it is not a classic caraway-scented aquavit, and Henrik Brinks has also included more modern types of the old spirit like the distillery’s variation infused with mulberry rose and another with cinnamon pepper.

‘Both these variations took off. I was surprised how popular aquavit became with many bartenders who use it in cocktails, and I, the old aquavit hater, now have an aquavit martini as my absolute favourite cocktail,’ says Brinks, who is zealous about restoring the image of Danish aquavit ‘as a spirit that does not bow to whisky, cognac, or any other foreign spirit.’

Copenhagen Distillery is just one of the dozens of new players on the aquavit market. At present, there are more than 20 distilleries producing aquavit along with others that do not actually distil, but use subsuppliers. The combination of fresh new players and historical brands has created a vibrant aquavit scene both in bars and restaurants.

One of the newest additions to the aquavit scene is Snaps Bornholm, which in record time after entering the market has gained a strong foothold. The company hails from the island of Bornholm, known as a gastronomic destination, and Simon Lorentzo, one of the founders, explains that the gastronomic angle was indeed a stepping stone.

‘We were absolute beginners in the aquavit business, amateurs who had been making our own herb- and fruit infused aquavits at home, deciding to give it a commercial try. This led us to

Bornholm, which is known for gastronomy and fine produce, something that the Michelin star restaurant Kadeau made us realize. Also, Bornholm is an island in the blue ocean, and our strategy has been exactly the same,’ he says, referring to the so called Blue ocean strategy, which pursuits differentiation, open up a new market space and create new demand.

‘Not that the aquavit market is by any means new, but our products are very different from the ones known already and this is very clear visually. Snaps Bornholm bottles looks different from the competition, and the taste is also different,’ says Simon, adding that the decision to only use organic ingredients differentiated the new player from the rest. Also they went to market withunusual tastes like hot chili, a combination of dill-cucumber, seabuckthorn, figs, rasberry-ginger-pomegranate and the ubiquitous Nordic acquired taste; licorice.

‘We wanted to give people an aquavit that they could really enjoy, which is why we chose these taste combinations, and we distributed special tasting glasses as well, to encourage people to treat the aquavit as something to enjoy carefully, rather than just chugging it down, which has been the traditional way to drink aquavit for hundreds of years,’ Simon Lorentzo explains. He does not say ‘cheers’ when he raises the glass but ‘sip!’ to underline that a glass of Bornholm snaps should be enjoyed slowly and in small sips.

‘Traditionally women tend to shy away from Danish aquavit, but with Snaps Bornholm it is different, so we have created a new market. And I think women have helped draw attention to the fact, that this aquavit can actually be enjoyed,’ laughs Simon Lorentzo.

And he is right about the enjoyment of aquavit being something rather new, as opposed to quickly downing shots of ice-cold spirit as is customary. Another proponent for the more connoisseur oriented style is veteran aquavit specialist Lars Kragelund.

Lars Kragelund is also a Food Specialist, and has put in a great effort to make people understand the true nature of aquavit as a companion to food, and he stresses that the pairing of different aquavits with the many different kinds of smørrebrød holds pleasures that can be compared to the pairing of food with fine wines: they complement each other.

And where Danish tradition calls for drinking aquavit as cold as possible and downing it like a shot, modern aquavit culture is more about sipping carefully to give the aquavit a chance to play with the food. For example, pairings might include caraway aquavit with fried herring on rye bread, dill aquavit with smoked salmon on white bread, the sweet-gale aquavit with roast beef, and oak-aged aquavit with beef tartare, or with the coffee instead of cognac.

Lars Kragelund is especially keen on the pairing of aquavit and herring.

‘Nordic raw materials are grown in a cool climate which often means more acidity and less sweetness, especially in our fruits. Our food traditions include classic preservation methods such as salting, pickling, and smoking in the processing of our raw materials,’ says Kragelund before laying out the ground rules for pairing aquavit.

‘The herring is a fatty fish that is processed according to the above principles. Whether served cold or hot, it tastes good with an aquavit because the alcohol helps release the aromas from the fish’s fats: a release that takes place in the mouth as we chew the fish and subsequently sip on the aquavit,’ he explains.

He moves on to discussing why the fat, sour, salty, and smoked tastes of herring go well with aquavit, saying that since ‘aquavit is sweet in its basic nature’, it ‘plays nicely the with sour, salty and smoked, slightly bitter tastes’ of many herring recipes. One pairing example is the classic marinated herring served with a ring of raw onion on rye bread along with a caraway aquavit. The marinade contains vinegar, allspice, anise, fennel, salt, and pepper, and the naturally matured herring has a taste of umami.

‘It is a very complex taste and scent experience,’ says Kragelund. ‘If you drink a caraway aquavit with marinated herring on buttered rye bread garnished with onion, you have a meal that is sensually complete; the basic flavour of the herring is slightly salty-sweet, which plays well with the aquavit’s sweet alcohol. The onion has a sweet after-taste, which goes well with the alcohol’s discreet and refined after-taste of anise and star anise. The spices of the marinade and the caraway of the aquavit play together and against each other – they simply lift each other up to new sensory heights. Last but not least, the grains and vinegar appear as were they created for each other. Individually, they may seem a little daunting to the untrained palate, but together they unleash each other’s beauty. However he suggests some caution for beginners:

‘The first time you try the combination of marinated herring and aquavit can, figuratively speaking, be compared to a strenuous hike in a rainforest with lots of mosquitoes and other bugs. Just when you are about to give up, the miracle happens. You enter a clearing where the trees give way to the sun and clear blue skies. Butterflies dance in the air, and you smell the flowers, all but forgetting your previous trouble. That’s how it feels when you start by taking a bite of the herring smørrebrød and a sip of aquavit. You close your mouth, swallow, and then you experience, perhaps not the first time, maybe not the second, but probably the third time, how the aromas of the herring dish and the aquavit cause the sensory forest clearing in your mouth. Once you have experienced this, you will never forget it.’

As an addition to Lars Kragelunds explanations, here are som some rules of thumbs worth remembering, when you drink aquavit. Number one is sip, don’t gulp. When you sip instead of gulping it down, you significantly enhance the experience. This is because your saliva contains water which enhances the aromas, it can be compared to adding a few drops of water to a glass of whisky. In addition, the temperature in the mouth is approximately 32 degrees celsius. This relatively high temperature helps to release aromas from the aquavit, as aromas are slightly volatile. If, on the other hand, you swallow the aquavit in one mouthful, then the amount of alcohol acts as a solvent and the mouth is cleared of the good saliva, leaving the mouth ‘chemically cleansed’ with an unpleasant burning feeling as a result.

The general rule is that clear aquavits should be enjoyed cold, and golden aquavits should be enjoyed at room temperature. Clear aquavits traditionally have a relatively high aroma content that can withstand being cooled without significantly loss of aroma. Golden aquavits traditionally have a lower aroma content, and in addition are often barrel-aged and therefore contain ‘heavier’ and less volatile aroma substances. These aromas must therefore be helped out of the product, and this is achieved with a higher serving temperature.

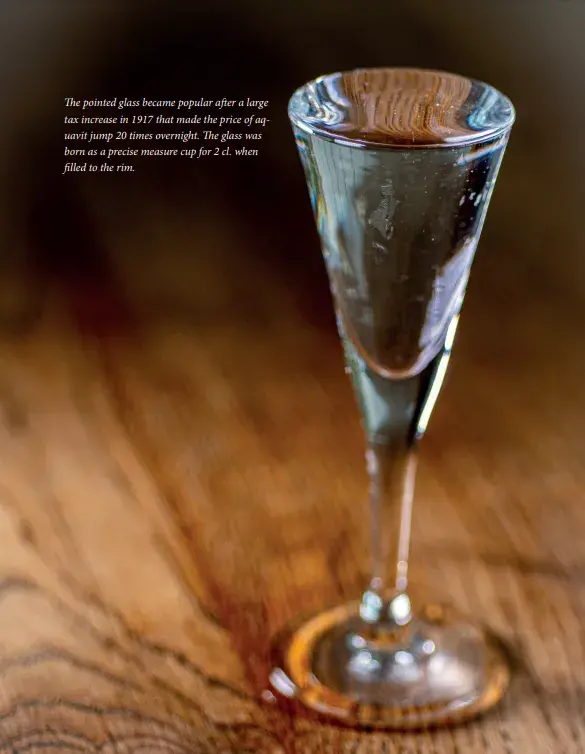

Clear aromatic aquavits should be enjoyed in small pointed glasses, and golden aquavits should be enjoyed in tulip-shaped glasses. With the higher concentration of spices in clear aquavit, this spirit is better suited to being served in the pointed glass. They have a very volatile aroma that, if served in a tulip-shaped glass which collects the aromas, would ‘burn off the nose’ when you sniffed the glass. On the other hand, the shape of the pointed glass lets the strong aroma concentration ‘run over the edge’.

Golden aquavits are born with slightly ‘heavier’ aromas because they have a lower spice concentration, and during storage in the wooden barrel, they form complex aroma molecules that are heavier and less volatile, which require the use of a tulip-shaped glass. The tulip-shaped glass makes it possible to swirl the aquavit, thus giving the liquid a larger surface from which its aromas can be released. In addition, the combination of the turbulence you create in the liquid when you move it plus the oxygen in the air also releases the aromas.