Smørrebrød is a piece of Danish cultural history. Its story is a fairy tale about how a simple everyday food was elevated to a coveted delicacy, gained worldwide fame, went out of fashion, then revitalized itself on its 100th birthday in order to achieve greater renown than ever before

Smørrebrød begins with bread. Usually, this is ‘rugbrød’ – or ‘rye bread’ – that also has a history in other European countries: from Norway, down to northern Italy, and east to Russia. We have the bread in common, but smørrebrød as a culinary speciality is a uniquely Danish phenomenon, and it has been with us since the Viking Age.

Archaeological excavations have shown that the Vikings ate bread and butter, but they left no written records of their diets. However, an Arab named Ibn Fadlan did. In 920, he was sent by the Caliph in Baghdad to observe the Vikings. He describes the food of the Vikings with some scepticism. He calls their favourite drink, mead, disgusting and wonders why the Vikings seem to prefer boiled meat to fried.

Bread was unleavened until the Viking Age, but the Vikings discovered sourdough and used it to develop rye bread, which is probably what is described in the Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar from 1250. The saga tells of a journey in which the weather was so cold that you could not spread butter on bread; instead, you had to bite the butter and the bread in turn.

In the following centuries, the Danes had rye bread as one of their most important sources of nutrition. Everybody ate it, but nobody paid it much attention. According to the earliest written source to mention it– theatrical plays by the important Danish writer Ludvig Holberg – rye bread was the food of the common people.

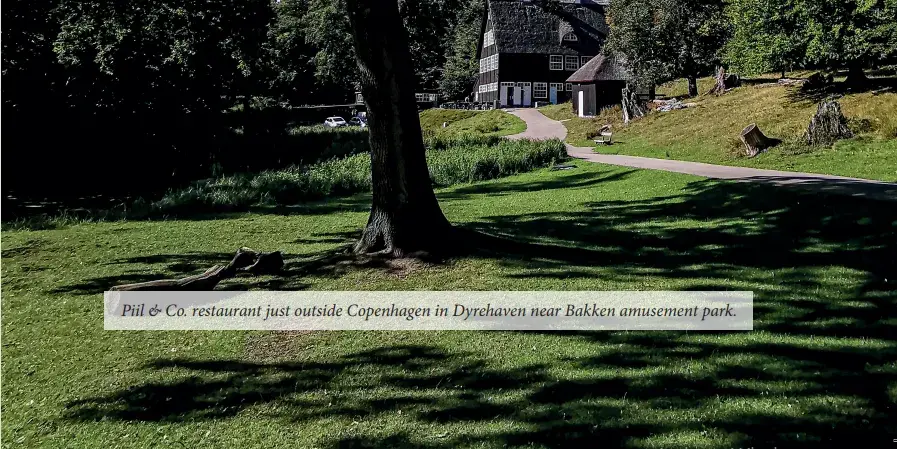

Holberg may well have eaten at some of the restaurants that to this day serve smørrebrød, such as Café Gammeltorv, which was founded in 1671 shortly before he was born. Holberg would have eaten smørrebrød of the simple type, for the establishments of the 17th century – inns – were by no means culinary oases. Nor were they, for that matter, in the 18th century, when a pub opened in Fortunstræde 4 where the Slotskælderen restaurant is located today.

Smørrebrød was not very appealing in those days, as was expressed by the poet Johan Herman Wessel’s in his famous verse from this period: ‘That love is not hate, and smørrebrød is not dinner, that’s what I know at the moment about smørrebrød and love,’ – which rhymes nicely in Danish.

This was a poem written in frustration, and there are two different explanations of its meaning. One says Wessel had been invited to a dinner party but served only smørrebrød. The other says that he rejected the bill at a tavern because it mentioned dinner on it even though only smørrebrød had been served.

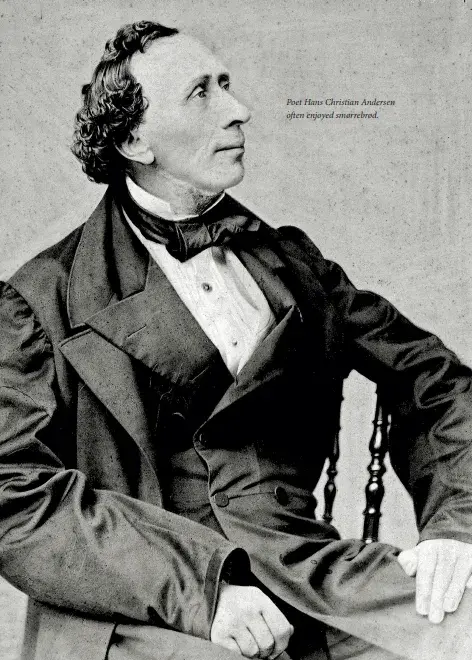

Another poet who commented on smørrebrød was Hans Christian Andersen. He often used smørrebrød as a kind of emergency measure if the food at a dinner party disappointed him, like the meals he ate at the home of the Ørsted family. They often served sweet fruit soup, which was something the poet despised: ‘We had sweet soup and duck; When I went home and was in the middle of Østergade I felt the nervous feeling I always get after eating sweet soup. I got as far as to the Henriques family, my feet wobbled, my hands trembled; I got two servings of smørrebrød and a cup of broth, it helped.’

Similarly, in his old age, Andersen could end up leaving a slightly too lively dinner party to eat smørrebrød alone, as he did in 1874 when he joined company in Holsteinborg but slipped out alone to enjoy ‘smørrebrød and Albani beer’.

The following year, Andersen would take his last breath and leave this world just before smørrebrød turned into a truly adventurous meal. But that’s still around the corner.

Smørrebrød’s major role in Danish food culture is well known, and it has been the subject of fierce passion. One example is found in the newspaper Fatherland. In the 19th century, the paper told the story of a boy, who had set fire to the farm, because the farmer refused him butter on his smørrebrød with cheese.

At the end of the 19th century, Denmark experienced a short gastronomic golden age which brought about the luxury version of smørrebrød. The golden age was sparked partly by the influx of French chefs, who started to gain influence in the newly formed upper class in Denmark. The new class was made up of merchants and industrialists who gained wealth thanks to the strengthening economy, and they were eager to socialise, which to a large extent happened around the dinner table.

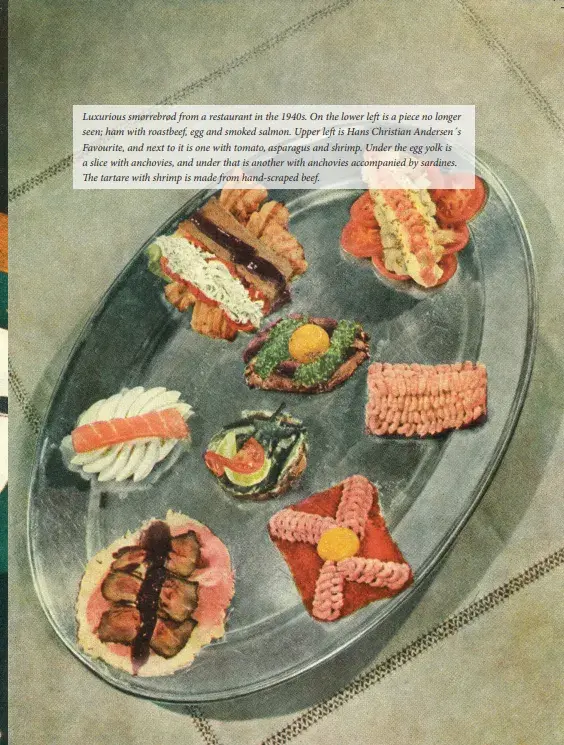

Inspired by fine French gastronomy, Danish restaurateurs brought the elaborate style of French cooking to Danish cuisine, thus upgrading the everyday smørrebrød to a luxurious feast.

For example, the duck roast and the pork roast came onto the table like neatly prepared pieces of smørrebrød with green salad under the meat and with red cabbage, prunes, and perhaps a slice of the new and exotic orange on top.

In particular, it was the idea of serving these very exclusive specialities on bread that attracted attention. Placing large amounts of meat on a thin slice of bread made luxury smørrebrød into something that stood out as a sumptuous meal. The prosaic smørrebrød of yesteryear continued to exist as an everyday food, but the luxurious version became more widely available in both new and previously existing smørrebrød restaurants.

Creativity flourished, and the selection grew. With fifty different variants of smørrebrød and as many guests, in any restaurant, a bright idea was developed to facilitate clarity: the smørrebrødsseddel. The smørrebrødsseddel was a printed form for guests to tick off their meal selection and hand to the waiter, an idea most restaurants adopted.

‘The art of smørrebrød is extremely interesting. For the expert, it is very easy to make, for the novice it is very difficult, like for a Dane to learn Greek, Latin or French.’

Axel Svensson, managing director of Oskar Davidsens, 1940s.

Smørrebrød’s status as something of national importance can be understood from an article in a Copenhagen newspaper of 1914, which was about 30 years after the emergence of luxury smørrebrød. The article, ‘Our Smørrebrød’, is a cry of alarm from a journalist upset by the price of smørrebrød in Tivoli Gardens:

‘The other day I was sitting at one of Tivoli’s best-known restaurants and was looking forward to having my dinner in the open air. I asked for a smørrebrød menu and got it. The first thing that caught my eye was a piece of smoked eel for the outrageous price of 0,50 krone and the same for smoked salmon. Of course, I did not ask for these, my favourite pieces of smørrebrød, as they were to be bought at such a crazy high price. It’s time for the audience to vigorously protest the exorbitant smørrebrød prices that all major restaurants are setting. At our restaurants, smørrebrød was once something that was really national. Foreigners as well as Danes delighted in the varied, nicely prepared, and tasty smørrebrød. It brought something festive to the meal,’ the journalist wrote about the modern national treasure, also praised by painters and poets, as shown on the following pages.

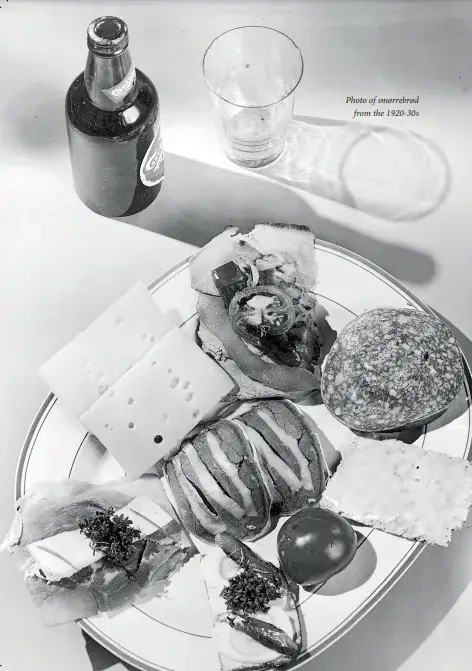

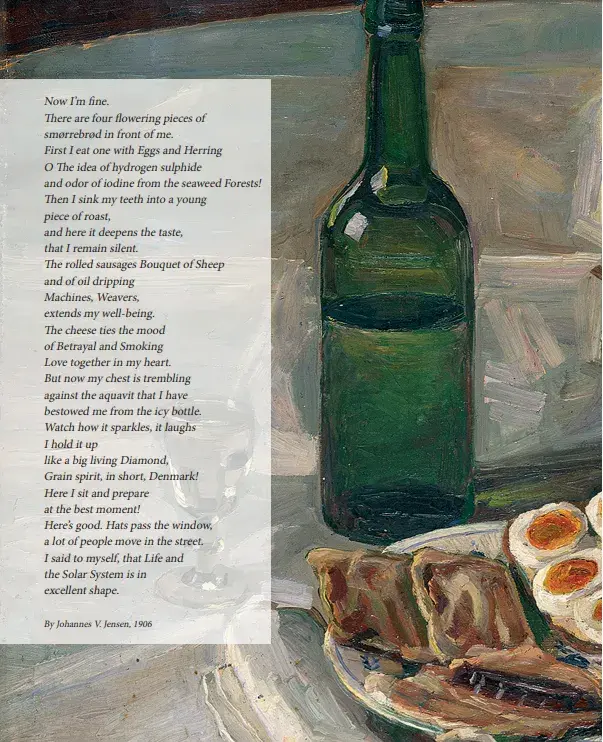

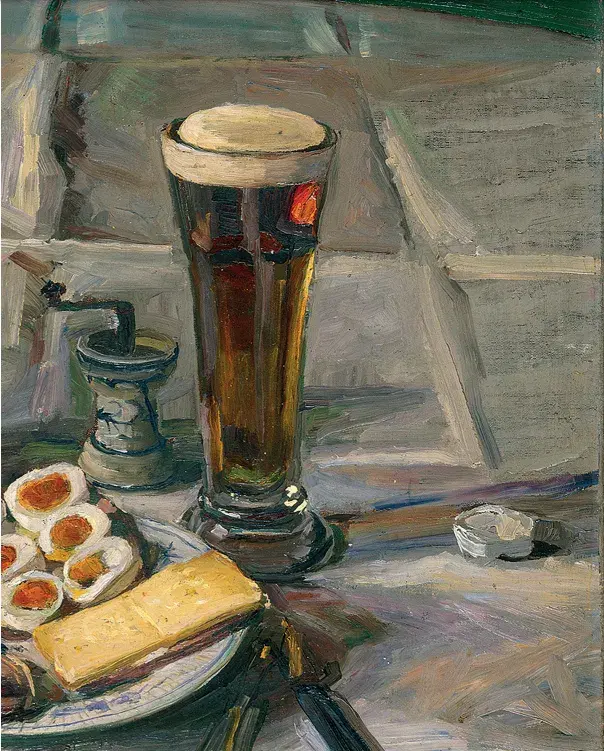

The smørrebrød described by Johannes V. Jensen in words, and by Fritz Syberg in paint, is not exactly luxurious, but neither were the type common people had in their everyday life.

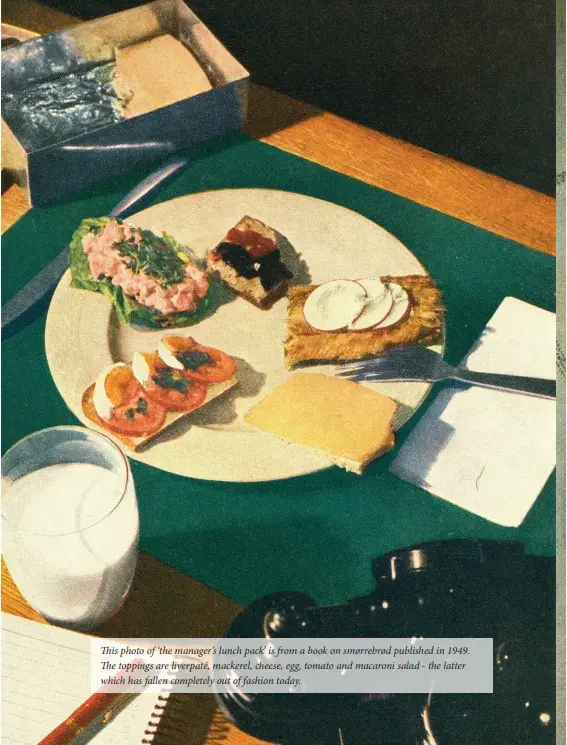

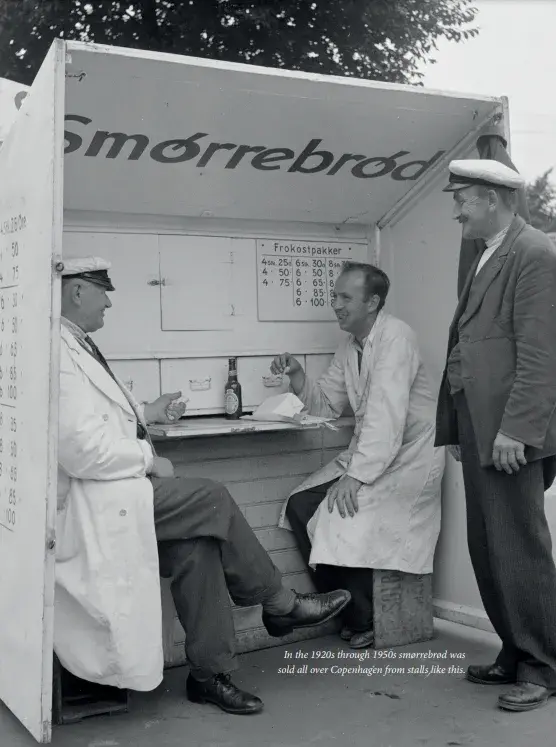

Luxury smørrebrød’s humbler sibling, ordinary smørrebrød, was the fast food of the day. It was sold on the street from horse-drawn carriages, stalls, grocery stores, and butchers, and entire smørrebrød factories arose with some producing up to 100,000 pieces daily.

A recipe from that time also show signs of simplicity, it was published in the newspaper Aftenposten. The recipe is for ‘herb salad for smørrebrød’, and it is made from carrot, celery, parsley root, potato, and beets. These are cooked and cut into small pieces, then turned into 40 grams of salad to top the bread.

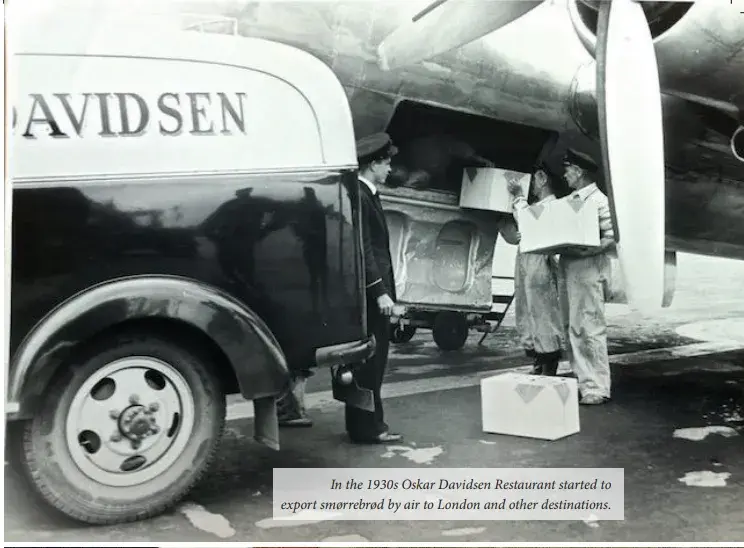

While some suppliers delivered their smørrebrød with a horse-drawn carriage, Oskar Davidsen trumped them by using motorcars and, in the 1930s airplanes to fly smørrebrød to international customers. As flying gained momentum, the smørrebrød followed along. For Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS), it became a kind of secret weapon in its competition with US airlines.

SAS invented the concept of economy class in 1952, and its smaller airplane seats and less luxurious service generated a level of success that American airlines had difficulty matching. In 1958, economy class became a new official price range, carefully standardized by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) with included rules on how much to charge for economy-class passengers. It was agreed that it would be acceptable to serve smørrebrød – or, to be precise, ‘sandwiches’ – as the economy-class meal as long as these meals were ‘simple, cold and not too expensive’. US airlines met these criteria.

But SAS chose to interpret the smørrebrød concept differently, and on the Scandinavian economy class, passengers were given 16 different kinds of smørrebrød to choose from. The US airlines protested, arguing that SAS thereby gained a competitive advantage. SAS responded by running advertisements proclaiming that ‘on our flights there is no indigestible rubber food wrapped in cellophane’. The ads showed photos of delicious smørrebrød that contrasted with US competitors’ cellophane-wrapped sandwiches.

The case resulted in the decision by IATA to impose a $20,000 fine on SAS, but the company was allowed to continue serving smørrebrød as long as the garnish did not cover the entire bread slice, leaving at least 2.5 square inches of bread visible.

If you flew to Los Angeles, you could continue the smørrebrød experience at the Scandinavian restaurant Scandia which was one of the city’s most popular places in the 1950s. Here, young Ida Davidsen was responsible for the smørrebrød. Back in Ida Davidsen’s home of Copenhagen, the old traditional inns serving smørrebrød were soon to come under pressure. Most were housed in the city’s old neighbourhoods where the sanitary conditions were poor, and this led to the demolition of many of the oldest houses in the 1960s. In some

cases, the old smørrebrød restaurants were granted an exemption and could continue until the owner retired. In the longer term, this still put an end to many places.

Poet Sigfred Pedersen, a regular guest at Husmann’s Vinstue, was among the voices that warned against the development. In the 1960s, Pedersen wrote that ‘these inns are precisely the best haven for people with upset nerves, for people fleeing the harsh realities of life,’ and ‘when they are closed down, a double-capacity psychiatric hospital will need to be built instead and paid for by the public.’

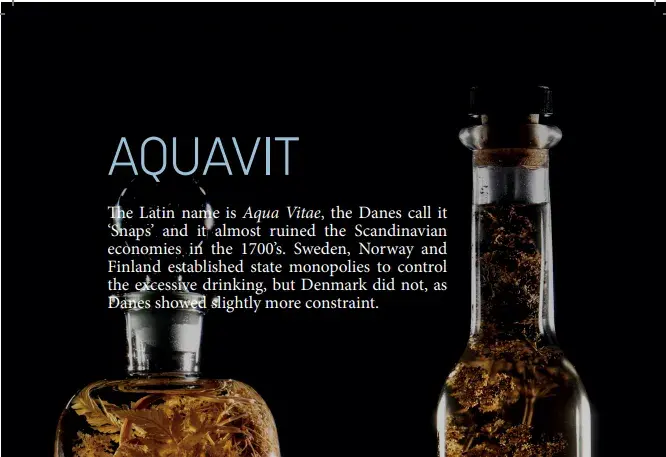

The decade brought even more changes. With the youth rebellion and the hippie movement, marijuana, wine, and exotic food became popular, while old-fashioned beer, aquavit, and smørrebrød gradually began to be perceived as outdated. During these years, more and more people started to take an interest in gastronomy, there was a focus on French cuisine, and smørrebrød seemed passé.

A third change was the industrialisation of food production, which meant that the supply of ready-made products grew significantly. Many restaurants stopped making their own products like sausages and mayonnaise since it was cheaper and easier to buy them ready-made. This trend meant that the quality of the smørrebrød was beginning to decline.

Customers also began to drift away in favour of hippie-style vegetarian food or fine French cuisine. The number of smørrebrød restaurants dropped, and these restaurants gradually disappeared from many provincial cities.

In 1971, Denmark’s first gastronomic magazine, Mad & Gæster (Food and guests), warned that the country was in danger of losing part of its culture in its quest for new foreign

restaurants. Jens G. Eilertsen, one of the most influential gastronomic voices of the time, described a visit to an Italian restaurant in Copenhagen:

‘The mood is emphasized by the waiters unnecessarily shouting the orders to one another, singing as just for his own pleasure, placing the minestrone in front of the wondering guest.’ Eilertsen argued that we should value the old Danish traditions instead:

‘Only one place has a local distinctiveness: the smørrebrød restaurant. It is Danish and characteristic of Denmark like the bistro to France, the pub to England and the trattoria to

Italy. It’s something we have for ourselves, the sand on the white wood floors, the oil-painted walls with Erik Henningsen’s sweating Tuborg man in a in a tobacco-blackened reproduction, rather than a fake Italian restaurant with chianti bottles hanging from the ceiling.’

In Copenhagen, however, there were still some bastions of old traditions left, with Oskar Davidsen Restaurant as the strongest. At this time, though, it also struggled, and the large

restaurant with several hundred seats had to close in 1974. Ida Davidsen continued the family tradition in a new and much smaller restaurant in a basement on Store Kongensgade.

She was synonymous with smørrebrød at that time, and in the decades when the dish was losing more and more ground, Ida Davidsen kept it alive. She was Danish smørrebrød’s foremost ambassador, and she renewed the speciality with great creativity and maintained a level of quality that was significantly above average.

When foreign media conducted interviews about Danish gastronomy, it was usually Ida Davidsen with whom they spoke. Her establishment was one of the country’s most important restaurant attractions. But her contributions aside, the 1970s was a bleak decade for Danish smørrebrød culture, and it was no longer a culinary experience to eat smørrebrød at a Copenhagen pub or lunch restaurant.

This was partly because industrialisation had eradicated many of the small craft companies that had previously supplied specialties to the restaurants. At the same time, guests were generally not discerning gourmands; in those years, Danes were more commonly concerned with low prices.

Such a climate does not create a breeding ground for quality, so for a long period of time, smørrebrød quality was low. In 1991, the aforementioned food writer Jens G Eilertsen noted that the smørrebrød situation was grave:

‘It is nowadays rarely a culinary pleasure to eat smørrebrød at a Danish restaurant, where the respect for Danish raw materials is absent. Well, the pork roast is usually reasonably

fresh, and the shrimp salad is taken from a can that is far from its expiry date. But the bread! The Danish rye bread, which once was a national pride baked in stone ovens and

proudly served, is today a sad industrial product that is mixed like cement and often tastes like this. After baking, it is frozen, with all the flavours killed off, so it is easier to cut.’

But early in the new millennium, something started to happen. After the French regime of the 1970s and 1980s, the fusion kitchen of the 1990s, and the molecular gastronomy of the 2000s, the concept of traditional ‘grandmother’s food’ emerged. Old Danish dishes – and old French recipes like sauce béarnaise – became popular in certain circles. And what was more natural than inviting the smørrebrød back into the game?

If in the 1980s Danes learned to frequent cafés like Parisians and drink espresso, now they were attracted to the smørrebrød restaurants that their parents had loved but they themselves had previously turned up their noses at.

Smørrebrød was a simple and common food up until the late 1800s, so there was no formal education in it before 1934. In 1962 the first school for ‘smørrebrødsjomfruer’ (female

chefs specialising in smørrebrød) was established. By 1973, four schools offered the two year long program, and graduated a total of 700 Smørrebrødsjomfruer.

In the 1970s smørrebrød’s popularity waned, and traditional chefs started to replace the specially-trained smørrebrød chefs. This shift was reflected in a new style, where form and size mattered more than substance

Their parents’ beer and aquavit began to appeal to the young. Slowly, the average age among the guests of smørrebrød restaurants dropped. And while in the 1970s through 1990s, mostly older people were found in these places, it became more and more common to see guests in their twenties and thirties.

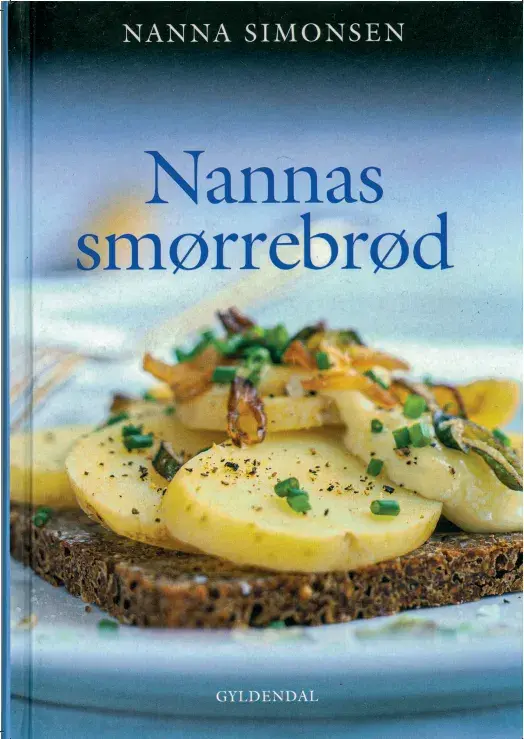

In 2000s a new style of modern smørrebrød started to appear, and it was best described by food writer and chef Nanna Simonsen in her 2001 book, Nannas Smørrebrød. In it, she advocates for a new type of smørrebrød that breaks with the style that had dominated from the 1970-90s, and that may have been one of the reasons for the dish’s decline in popularity.

The traditional chefs, who took over many of the smørrebrød chef positions tended to overdo things, which resulted in smørrebrød with enormous amounts of garnishing. Furthermore, the quality of the produce they used was often not high because of the demand for low prices. Nanna Simonsen criticised this development in which the form of smørrebrød seemed more important than the substance.

‘If the bread and toppings are not of the highest quality, the phenomenon of smørrebrød belongs to gastronomic atrocities, and not to the authentic smørrebrød, which is Denmark’s only and most important contribution to the world gastronomy,’ she wrote in 2001. Coincidentally, this was two years before Noma Restaurant would begin its voyage to worldwide fame and recognition, adding New Nordic Cuisine to the world’s culinary heritage.

The smørrebrød recipes in Simonsen’s book led the way for a more modern take on smørrebrød: one where the garnishing was almost completely stripped, leaving only the main ingredients. In her recipe for a piece with smoked salmon and potatoes, for example, she stressed the importance of cooking the potatoes al dente, and the style she presents is very close to the modern style that would start to win influence in the late 2000s.

One of the first, if not the very first, new places that seemed to follow Simonsen’s suggestions was the restaurant Told & Snaps. It opened in 2000 with smørrebrød chef Helle Vogt in charge of the kitchen, and she later left to revive the historic Tivoli Hallen restaurant, which then also joined the elite. Another remarkable change was, that a gourmet restaurant, Leonore Christine in Nyhavn, put smørrebrød on the lunch menu, by the way with Karina Pedersen – later a star at Schønnemann, Palægade and Møntergade – in charge.

The first steps towards a modern style came in 2001, when cookbook author Nanna Simonsen argued for more simplicity and better quality.

The most influential innovation came in 2006, when young chef Adam Aamann opened the doors to a smørrebrød shop with seating in Copenhagen’s Østerbro neighbourhood. Here you could find smørrebrød of a whole new calibre that was based predominantly on organic ingredients and executed in a tight, unadorned style emphasizing high quality.

So far, it had not been common – or smart – for young ambitious chefs to settle on smørrebrød. It was Adam Aamann who made it legitimate for chefs to move into the smørrebrød category.

In 2007, another important event occurred: a change of ownership at the restaurant Schønnemann, which had not hitherto been known for anything out of the ordinary. This was changed by the new owners John and Søren Puggaard who, by switching over to top quality ingredients, raised the bar for how delicious a piece of smørrebrød can be.

Smørrebrød came back into fashion and played a growing role as Danes started to eat out more than before. Its new popularity made it possible to gradually divide the smørrebrød category into subcategories of classics and modernists. In the following years, encouraged by the growing interest in gastronomy overall, development took off, and Copenhagen gained a number of ambitious new smørrebrød restaurants.

When Noma began to attract many gastronomic tourists to Copenhagen, restaurants like Aamann, Schønnemann, and Skt. Annæ also got a lot of attention in the international press. Gradually, a pattern began to emerge: tourists would come to Copenhagen to eat at the top gourmet restaurants Noma and Geranium, and while they were at it, they would end up trying a couple of smørrebrød restaurants too.

Some years later, the provinces were also blessed with new smørrebrød restaurants of gourmet quality, and today, gourmet smørrebrød in most parts of the country. As a culinary speciality, smørrebrød has never been stronger.